“What is imagination?,” asked Eli Siegel in a lecture of 1952, and he explained:

"One of the answers to that question is: imagination is that which changes the world in order to see better what it is. The other is what changes the world in order to make us better able to live without it; that is bad imagination."

I’ve learned that our imagination is working well when we use it to think about the world and people deeply and fairly. But there is that in every man that can use his imagination badly--to alter the world into something smaller and uglier, a world he

has the right to feel superior to and have contempt for. This contempt hurts a man’s life very much.

I. Two Ways of Seeing the World

Early, one of the things I most liked to do was read stories about children in other times and lands. As I imagined what a boy felt growing up at the time of Alexander the Great, or during the Revolutionary War, I had a sense of wonder about people and a world different from the one I was accustomed to.

But I also spent a lot of time using my imagination to collect hurts and grievances. Writes Mr. Siegel in Self and World:

"One of the earliest and most frequent things that can happen to a human mind is to see the world as inimical."

The person I used most to feel the world was against me was my father, Sam Weiner. It never occurred to me to think about his life, for example, as a teenager growing up during the Depression, or as a WW II soldier, or as a husband and father who worked very hard to support his family. Instead, in my mind I turned him into a tyrant whose chief purpose was to make me suffer, and deny me all the things I spent much time dwelling on that I didn’t have--a home in the suburbs, fancy vacations, expensive summer camps. This mean and cold way of seeing my father hurt him and had me dislike myself very much.

Aggrandizing myself was another frequent way I used my imagination. I envisioned the ecstatic reviews for the autobiographical play which I would one day author, and, of course, star in, reviews that said things such as—“a masterpiece of self-perception.” And I’d imagine the many awards that would be bestowed upon me. The high point of the play would be a dramatic monologue on a darkened stage with a spotlight on me. You may be asking what I said in it, but since I never actually wrote any words to my play, I can’t tell you.

I used both getting hurt and puffing myself up to feel I would be “better able to live without” the world and people. By the time I was eighteen, I had few close friends; and a recurrent dream was my being alone in a cabin in the Catskills enveloped by snow.

In his lecture, Mr. Siegel explains:

"The first thing we need in imagination is to get away from what we are for the moment and see adequately what we are not."

To “see adequately what we are not” is to put our egos aside and use our selves to have a strengthening effect on other people. This is good will, and I didn’t have it. It was nearly impossible because of my large self-absorption, my feeling, as it is put today, that “everything was about me.” For instance, in an early consultation, I was asked: “Do you resent the pain of other people?” “That I cause it?” I asked. “No, that they have it.” “That they have it?” I repeated. And I saw that I actually did resent it.

As I will tell of, I’m glad to say that my ability to think deeply and imaginatively about people has increased a good deal through my study of Aesthetic Realism.

2. “Dreaming With His Eyes Open”

I tell of now about some aspects of the very rich life and work of the Mexican artist Diego Rivera.

In Self and World, Mr. Siegel wrote:

"We all of us have pictures of the world in our minds—and these pictures are of imagination; the beauty and rightness of these pictures depend on how much we can see the world as what it is."

Because of the way, as artist, Rivera used his imagination to see the world as “what it is”—as a relation of good and evil, wonder and ordinariness, human feeling and abstract shapes, many of his works have a large “beauty” and “rightness” which make him one of the important artists of the past century.

Diego Maria Rivera was born, along with a twin brother, in 1886 in a small town in central Mexico. His heritage was amazing; that is, he was of Mexican, Spanish, Indian, African, Italian, Jewish, Russian, and Portuguese descent.

Before the age of two, his brother who was sickly from birth, died, and his mother had a nervous breakdown. After this, it seems she turned her affections to Diego in a way he found stifling. He had the question every child has, and this is a question about imagination, how much did he want to think about what his mother felt? From what his biographer tells of in "Dreaming With His Eyes Open: A Life of Diego Rivera", it seems not so much. Patrick Marnam writes:

"[In all his years] Diego almost never mentioned his mother except in belittling or dismissive terms."

It can be asked: Did the scornful way Diego saw his maternal parent affect badly how he would come to see all women? Marnam indicates that this was so. He says:

"Rivera’s emotional elusiveness [from his mother] was to become a distinguishing feature of his adult life."

But imagination also worked in a very different way in the young Diego. He writes in his autobiography "My Art, My Life":

"As far back as I can remember, I was drawing. Almost as soon as my fat baby fingers could grasp a pencil, I was marking up walls, doors, and furniture. To avoid mutilation of his entire house, my father set aside a special room where I was allowed to write on anything I wanted. Here I made my earliest 'murals'.”

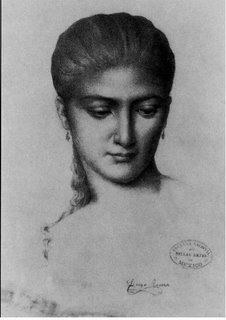

By the age of nine, he was very adept at sketching; two years later, he was attending art school full-time. Here is a very deep and thoughtful portrait of a woman he did at the age of twelve:

In 1907, he left Mexico to study in Europe, and spent much time in Paris. There, the great Picasso befriended him and saw value in his work. For awhile, Rivera became a Cubist and gained some notice. This is his most famous work of that time, “Zapatista Landscape”:

And here is a portrait he did of himself at age twenty.

As Diego Rivera traveled about Europe, he became aware of poverty in a way he hadn’t been before—how people had to sleep under bridges, and scavenge for food. What he saw was to have a profound effect on his future as artist. He said of himself at that time:

"I now had a vision of my vocation—to produce true and complete pictures of the life of the toiling masses."

But it was not until he traveled to Italy to see the frescos of Giotto, did he find the technique he wanted to work in.

After spending many years in Europe, he felt he needed to return to his homeland. When he did, something very deep happened to him inspiring his artistic imagination. He wrote:

"In everything I saw a potential masterpiece—the crowds, the markets, the festivals, the workingmen in the shops and the fields—in every glowing face, in every luminous child. All was revealed to me. I had the conviction that if I lived a hundred lives I could not exhaust even a fraction of this store of buoyant beauty."

3. The Murals of Rivera: Warmth and Abstraction

Soon, Rivera began to receive commissions to create murals for buildings in Mexico. One of his greatest works was for the Ministry of Education in Mexico City which consisted of 128 individual panels on three floors covering a total of 17,000 feet that took him over four years to complete. Here is one section of the building:

And here are three of his panels:

He himself said of them: “Each fresco was individual and separate in itself, yet all were interrelated.” He used his imagination to show human beings who had been subjected to such poverty and neglect, who had been horribly misused—as having grandeur and nobility.

In a lecture, Mr. Siegel said:

"To see what many people feel is already a job of imagination which most people have given themselves the privilege of not doing."

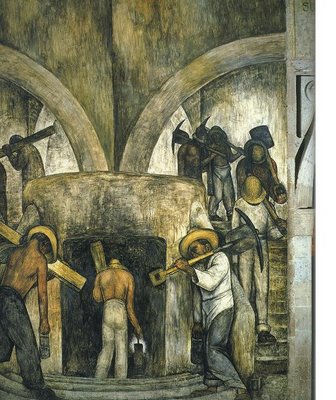

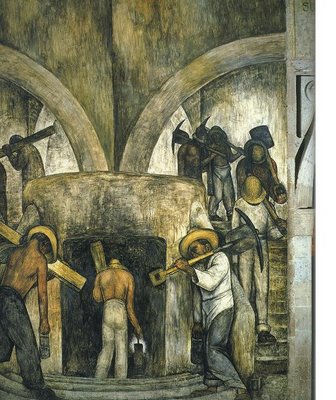

This kind of imagination is what Diego Rivera was going after in his murals, including this one entitled “Entering the Mine.”

Here, miners descend into what was called the “mouth of hell.” Rivera gives these “toiling masses” dignity, even religious meaning: with their shovels and wooden beams, they have a relation to Christ on the cross; their sombreros are similar to the halos of Giotto.

I think a central pair of opposites in Diego Rivera's murals is personal and impersonal. Eli Siegel asks about them in “Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?”:

"Does every instance of art and beauty contain something which stands for the meaning of all that is, all that is true in an outside way, reality just so?—and does every instance of art and beauty also contain something which stands for the individual mind, a self which has been moved, a person seeing as original person?"

In customary life—and I know this from personal experience—a man can not want to see large “meaning”, or be “moved” by the reality of another persons. This makes us mean, and robs us of emotions we’re desperately hoping to have.

In "Entering the Mine", there is much humanity and pain, but there is also the abstract forms and directions of “reality just so”: the miners and their tools form an oval shape. Look at the man in the bottom center surrounded by darkness. His isolation is interrupted by the lit lamp, and he is joined to the other men by the diagonal lines of their tools. The plank he is holding is a continuation to the arch above. These arches, along with the upward thrusts of the tools, counteract the downward motion of the work. The self of Rivera was “moved” by the plight of these miners, and we in turn are “moved” also—and educated.

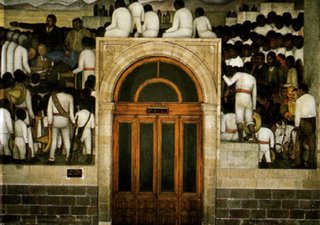

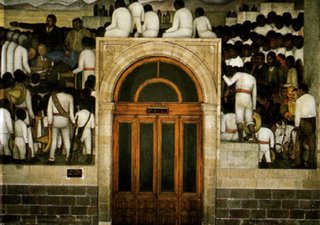

These are some other murals that I see as very good because of how powerfully they put together impersonal and personal, human feeling and abstraction: “The Burning of the Judases”:

Here is the “Festival of the Distribution of the Land.” Look at how Rivera had people sitting (and one child standing) above the door. That took wonderful imagination!

And these two are of the Mexican revolutionary hero, Zapata, and both are very fine.

However, in some murals there is a crowdedness of figures that I think hurts the composition. Take for instance, “Friday of Sorrows”:

I think the “Day of the Dead is a mingling: the skeletons on top are very lively but again the bottom of the work is too busy.

Rivera loved the earth and people of Mexico, and saw them as deeply of each other. He said: “The land belongs to everyone like the air, the water, the light, and the heat of the sun.” And he hated how the conquistadors with their desire for profit at all costs, made for a horrible sundering, enslaving millions of Mexicans for the enrichment of a few.

We can see his feeling in this beautiful mural: “Crossing the Barranca” in which Spanish conquerors drive Indians, some of them already slain, across a deep gully.

Intertwined with branches, many of them in brightly colored clothing are hanging onto the branches for dear life, lest they fall into that abyss.

At the bottom is a very surprising being: part-human, part-animal, and it is wailing in protest at this horrible scene.

All this is surrounded by a blue sky, mountains, and lush green foliage. We feel the richness and vacancy of reality, its “buoyant beauty” and confusion, the separation and togetherness of men and nature.

4. Rivera and Women: Too Much Imagination, and Too Little

In his definition of kindness, Mr. Siegel explains: “To be kind, we must have the imagination arising from the knowledge of feelings had by others.” In his murals, Rivera was kind as he thought about the effect hundreds of years of imperialism had on thousands of his fellow countrymen.

But this kind imagination was much lacking in him in his relations to women. He was married four times and had many to do with many women, including with photographer Tina Modotti, and actresses Dolores Del Rio and Paulette Goddard.

The woman who affected him most was his third wife, Frida Kahlo. Their 25-year relationship was a complex and agonizing mingling of respect and contempt, dependence and defiance, and as his biographer writes, “idolization and neglect.”

They met when she was just fifteen, and Rivera, 36. A few years later, Frida was badly injured in a bus crash, became bedridden, and then took up painting. One day, she went to him and spoke in a way that I’m sure made for respect in Rivera. Asking him to look at her work, she said: “I have not come to you looking for compliments. I want the criticism of a serious man.” This, along with her pride in her Mexican heritage, her passion about the inequities in her land, and her vivacity, affected him very much. He said of Frida: “Her sparkling presence filled me with a wonderful joy.” After a brief courtship, they wed. Here is a photo of them at a May Day parade in 1929:

But there was something in Rivera that was against having a large, sweeping, respectful emotion about a woman. In a class, when I spoke coolly about a woman I respected and who had deeply affected me, Ellen Reiss asked me: “Do you think you now want to show that she’s not so necessary to you, and that you can take or leave her?” I saw that this was my purpose.

This ugly use of imagination became Rivera’s attitude to Frida; it took a very mean form. Just after a year of marriage, Rivera began having affairs, including with some of Frida’s closest friends. Meanwhile, Rivera despised himself for this. He wrote: “And what sort of man was I? I had never had any morals at all and had lived only for pleasure where I found it. I was not good.”

Every man needs to ask: Do I use my imagination to try to be fair, or for some other purpose? Some time ago, I met a woman and very quickly felt she “fit the bill” and I began to make my “plans”: forming the guest list for our wedding, and looking for a new apartment--even though we had gone on just one date. When I told of this in a class, Miss Reiss said to me:

There has to be a large enough desire to know a person before deciding if she “fits the bill.” Otherwise, we are looking for someone to fulfill a function of ours. If we have to do with a person and are not interested in knowing them, what are we interested in?

I saw that I was using a woman for self-love, and no woman wants to be used this way. What a woman is most hoping for from a man, and what I’m asking for from myself, is to use my thought, my imagination, to try to understand. Becoming increasingly clear about this has made for a new happiness and confidence in me.

At his kindest, Diego Rivera encouraged Frida Kahlo in her art, and was pleased when she received recognition. But I also think he had contempt for Frida’s idolization of him. “You are my life itself,” she wrote to him, “and nothing and no one can change this.” At a time a woman acted as if she needed me very much, Mr. Siegel asked me “Do you have a kind of power over her that is detestable?” I did, and I think that the callous way Rivera treated his wife shows that he did too. Marnam writes how he was “possessive” and “overbearing” at one time, and then so neglectful even as she was in great physical pain from her earlier accident. Writing critically of himself, Rivera said:

"If I loved a woman, the more I loved her, the more I wanted to hurt her. Frida was only the most obvious victim of this disgusting trait."

I think the unjust way Rivera used his imagination as to women hurt his imagination as artist. His depictions of women are various, but some are clearly not good. Take for example, this one in which a woman is made to look smooth and cold, not as having the true depth and richness of reality in her.

None I have seen is as deep or as moving as the one he did when he was twelve.

I end with a work that has a relation of the "toiling masses" and "buoyant beauty" that I care very much--“The Flower Carrier”:

In this somber but lush work, an Indian wearing a yellow hat that partially hides his face is kneeling on the ground, weighed down by a large basket of flowers, and holding himself up with his columnar-like arms. An abstract yellow band of cloth connects his heart to her heart. She is gentle and strong as she uses her body to try to ease some of his burden. I believe the largeness of the figures on the canvas is a criticism of the small, insignificant way people such as these were seen. And the irony is that because of the economic exploitation of the land and people of Mexico, these lovely and delicate flowers that stand for a kind earth have been turned into a source of pain and oppression.

The life of Diego Rivera—his fineness as artist, his unkindness as a man and a husband—is evidence for the crucial difference between good and bad imagination. It is the difference that Aesthetic Realism is teaching me and can teach every man to recognize so he can make a proud, wise choice for his life.